Support for emergency response planning by the UN humanitarian clusters – Round 4

1. Introduction

Overview

Sajag-Nepal is a UK-funded multidisciplinary research project examining the use of local knowledge and new interdisciplinary science to inform better decision making and reduce the impacts of multi-hazards in Nepal. The project involves a team of researchers and practitioners from Nepal, the UK, New Zealand, and Canada, including the UN RCO in Nepal. The research aims to make a significant difference to the ways in which residents, government, and the international community take decisions to manage multi-hazards and systemic risks. A key objective is to establish a robust evidence-based approach to strengthen the national-scale strategic planning for complex multi-hazard events through the UN Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) Cluster Emergency Response and Preparedness Plans (ERPPs).

Following three previous rounds of engagement with the UN HCT clusters in April, September 2022, and April 2023, a fourth round of workshops was held in September 2023. The workshops were intended to share the outcomes from the last rounds of workshops, to present the first results from new monsoon multi-hazard scenario ensemble modelling, and to continue to explore how our risk models can be tailored to each cluster’s specific needs. It is expected that this iterative process will result in a more robust and efficient ERPP framework.

Focus group arrangements

As part of the round 4 engagements the research team held semi-structured focus groups with the clusters to share the preliminary findings of the multi-hazard risk modelling. The design of the focus groups was based on thematic similarities, tasks, organisations, and actions undertaken by each cluster as part of their corresponding ERPP. The groupings of the clusters and the schedule are indicated in the table below. There were a total of 31 participants representing the 11 clusters.

| Clusters | Date | Time |

| Logistics, ETC, & WASH | 13 September | 1000-1200 |

| Health, Nutrition & Early Recovery | 14 September | 1000-1200 |

| Protection, Education, Shelter & CCCM | 15 September | 1400-1600 |

Each focus group began with a brief introduction of the Sajag-Nepal project and the objectives of the workshop from the lead project investigator, Prof. Alex Densmore. This was followed with a debrief of the previous rounds of workshops and then sharing and discussion of the risk modelling outputs. The program was audio recorded and minuted with the consent of the participants.

2. Focus group summary

The major focus of the workshop was to discuss the 2023 seasonal monsoon forecast and compare it to the actual impacts in Nepal through early September, as well as sharing the first results from the monsoon multi-hazard scenarios on the basis of a 14-day sub-seasonal rainfall forecast. For the multi-hazard scenarios, impacts on buildings and roads were estimated due to both landslide occurrence and debris runout.

Comparison of seasonal forecast with actual impacts

The seasonal monsoon outlook (June-September) issued by the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology (DHM) is used as the basis for monsoon ERPPs by the government and the humanitarian agencies. The 2023 monsoon seasonal outlook showed anticipated monsoon rainfall over eastern and southeastern part of the country at close to average, while the rest of the country was likely to be drier compared to an average monsoon year. The clusters generally considered this information valuable, but they noted that the outlook only provides limited information at the beginning of May, and it is not updated later during the monsoon season. Considering this, the team worked on providing additional information to go alongside the seasonal outlook. Based on the last 20 years of monsoon rainfall from 2001-2021, the team identified the year for which observed rainfall was most similar to the outlook, in terms of the spatial pattern and anticipated amount of rainfall. For the 2023 outlook, the expected pattern of rainfall most closely matched the 2019 monsoon. This analysis cannot anticipate specific patterns of impact but may provide a way to relate the forecast with real historical events and with the experiences of the clusters. Both the seasonal outlook and the observed pattern of rainfall in 2019 were then compared with the actual impacts experienced in 2019, as well as those experienced in 2023 to date as recorded in the Bipad Portal.

The majority of cluster representatives agreed that the additional information along with the DHM seasonal outlook would be useful to foresee the potential level or scales of impact in the coming monsoon. Some clusters noted, however, that many of the largest monsoon impacts in recent years occurred in isolated storms that are not reflected in the seasonal outlook, which only contains information on the average total rainfall expected across the season. They also noted that there are variations between clusters in terms of historical ‘memory’ of past monsoon impacts; some staff have experience of working in response to severe past events and could recall what had occurred, whereas other staff were new to the role or cluster and lacked that experience. These points represent important limits on the usefulness of the seasonal forecast to reflect localized events and their impact. Finally, clusters indicated that updates to the seasonal outlook on a monthly basis would be very useful as a way of updating their ERPPs; these updates are issued by SASCOF but are currently not re-released by DHM, and the team agreed to explore ways in which this updated information could be presented to the clusters.

Monsoon multi-hazard scenarios and discussion

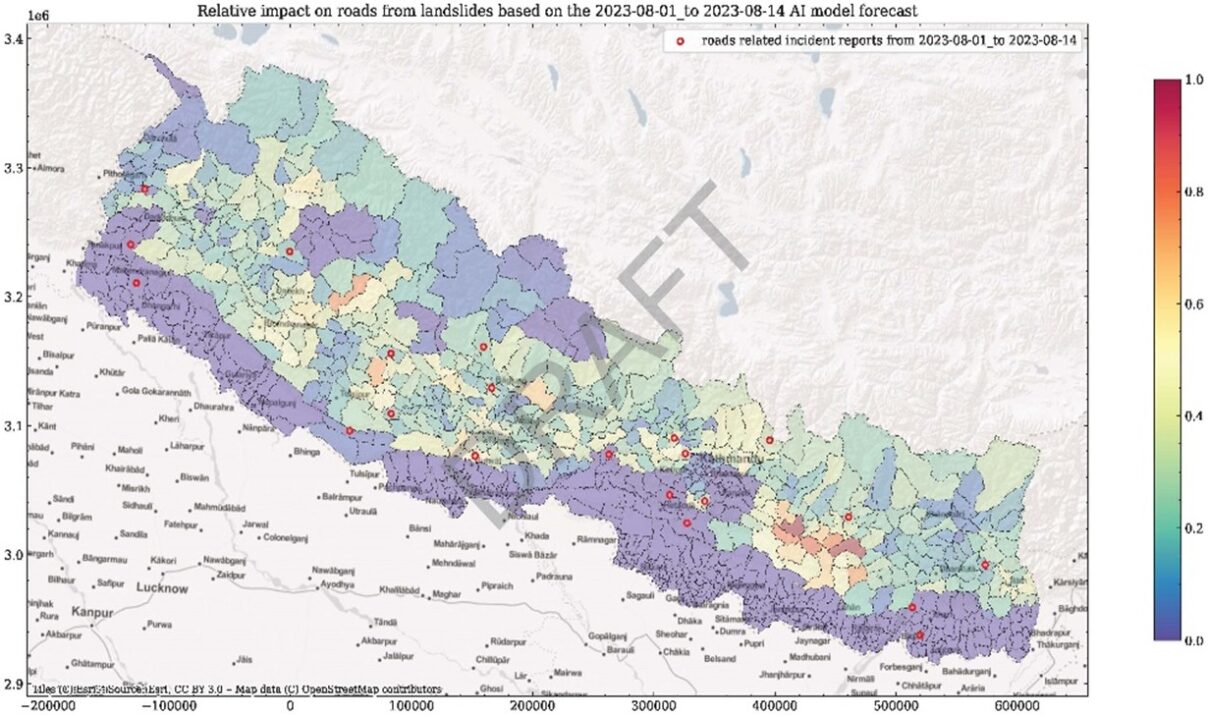

An example of a monsoon multi-hazard scenario was shared with cluster members during the workshop. The scenario was developed using an AI model to convert the 14-day rainfall forecast for the period of 1 August to 14 August 2023 into a map of districts where landslides and debris runout are expected to occur, based on events since 2011 recorded in the Bipad Portal. In those districts, a second model is used to anticipate the impacts of landsliding and debris flows. Two different scenario results were presented: one with relative impact on each building due to landslides, and the other with the relative impact on roads due to landslides. Impacts were aggregated at the municipality level to provide a ranking of municipalities that are more or less likely to be impacted by that pattern of rainfall. The ranking was then overlain with incidents that occurred within that two-week window, again taken from the Bipad Portal, and scaled by the number of households affected. The scenario results are shown below in Figures 1-2. This led to open round table discussion on how these model results align with the current monsoon ERPPs, if there are areas where the ERPP aligns with the scenario results as well as areas where it does not, and how the results could be improved and made more useful. All the clusters indicated that the two-week window covered by the monsoon multi-hazard scenario would be very important, considering that at present only seasonal and 72 hr information are released by the DHM. The clusters further highlighted the limitations and uncertainty of the seasonal forecast, as discussed previously in the third round of workshops, as well as the difficulty in responding to a 72-hr forecast, meaning that information between these two timeframes would be very useful. Also, as little attention is given to landslide hazard in the contingency planning process, the scenario would be useful for identifying areas of high landslide risk and prepare accordingly.

A major part of the discussion focused on the uncertainties of the model results. While the scenario could be useful to identify the spatial pattern of potential multi-hazard impacts, there are important uncertainties associated with the results. The team explored the impact of these uncertainties with the clusters, focusing on two different kinds of errors. ‘False positives’ will arise in areas where the risk model predicts that impacts are likely, but none occur during the 14-day forecast period, whereas ‘false negatives’ will arise in areas where the model predicts little impact but major effects do occur during that time period. These uncertainties were discussed with the clusters to understand their effects on decision-making and the preparation of the ERPPs. Most of the clusters were not particularly concerned about the uncertainties as, irrespective of cluster being prepared for impacts in certain areas, the cluster member organizations can be mobilized to respond to the affected area. In this way, the scenario acts as more of a ‘trigger for preparedness’ of the clusters rather than determining the specific response to an event. False positives were not seen as problematic, because any preparedness activity in itself was seen as useful, whereas false negatives were identified as a more significant issue. There was some discussion of whether a series of false results in the scenario would lead to a breakdown of trust with cluster members, but there was no consensus among cluster representatives on this point, possibly as this has not been experienced to date.

The team also discussed the ways in which cluster leads and cluster members could potentially use the monsoon scenarios in their preparedness activities. Clusters were nearly unanimous in suggesting that the scenario results would be useful in communication and building up or allocating human capacity, rather than building up physical capacity (e.g., in terms of equipment or emergency supplies). The clusters identified several distinct actions that could be taken on the basis of the scenario results, including: notifying and alertin cluster members in the municipalities that were identified as higher risk, appointing staff to particular locations, bringing forward training exercises or drills, ensuring sufficient capacity to respond in those areas as well as in neighbouring municipalities, cancelling or re-arranging staff leave, and awareness-raising with municipal governments.

The ensemble results that were shared with the clusters were limited to building and road impacts at municipality level which can be further aggregated at the district or province level as per the requirement of the clusters. Considering the spatial resolution and level of aggregation of the scenario ensemble results, clusters agreed that aggregated information at federal level is needed and with the provincial level contingency plan being prepared, the representation of these scenarios at provincial level would be equally important. They also highlighted that, with the mandate for the local government to develop their own disaster preparedness and response plans, risk information at the local level would be useful for their planning process irrespective of the uncertainties. Most clusters preferred the information to be categorised into high-medium and low impact areas as an indicator of the level of preparedness and response needed. We also discussed the integration of other attributes relevant to the clusters into the model, such as rural roads and trails, critical facilities such as hospitals and health centres, emergency shelters, schools, WASH facilities, communications infrastructure, market areas and open spaces. This is certainly possible within the model framework, as long as there is spatial information on the location of these facilities.

Finally, the discussion explored the potential for testing the result with the cluster at federal level and laying the groundwork for the information flow to provincial or other sub-national levels.

Conclusions and next steps

The focus group meetings were valuable to understanding the preferences of the cluster especially on the combination of level of information, spatial resolution, and attributes that can be incorporated into the monsoon multi-hazard ensemble model in future. The meetings also provided insight on what additional supportive information along with the DHM seasonal outlook could be supplied to support the preparation of contingency plans. The research team will use this information to refine the multi-hazard scenario and risk modelling, in order to generate the scientific evidence to support each cluster in preparing effective and improved ERPPs. Following the discussion, the team will work on providing an initial set of impact model results based on the 2024 monsoon seasonal outlook, that could be used in next year’s Monsoon Response Preparedness Plan. The team will also work on developing a ‘pipeline’ to enable the 14-day sub-seasonal forecasts to be rapidly converted into rainfall impact scenarios during the 2024 monsoon, Finally, the team offered to meet with representatives of interested clusters in early May 2024 to work through the seasonal outlook with them and discuss in detail how to incorporate the anticipated impacts into the 2024 ERPP.