Support for emergency response planning by the UN humanitarian clusters – Round 3

1. Introduction

A key objective for Sajag-Nepal is to establish a robust evidence-based approach to strengthen the national-scale strategic planning for complex multi-hazard events through the UN Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) Cluster Emergency Response and Preparedness Plans (ERPPs).

Following two previous rounds of engagement with the UN HCT clusters in April 2022 and September 2022, a third round of workshops was held in April 2023. The workshops were intended to share the outcomes from the last two rounds of workshops, to present the first results from new earthquake multi-hazard scenario ensemble modelling, and to continue to explore how our risk models can be tailored to each cluster’s specific needs. It is expected that this iterative process will result in a more robust and efficient ERPP framework.

2. Focus Group Arrangements

As part of the round 3 engagements the research team held semi-structured focus groups with the clusters to share results derived from rounds 1 and 2. The design of the focus groups was based on thematic similarities, tasks, organisations, and actions undertaken by each cluster as part of their corresponding ERPP. The groupings of the clusters and the schedule are indicated in the table below. There was a total of 45 participants (34 male, 11 female) representing the 11 clusters along with representatives from NDRRMA and UN OCHA.

| Clusters | Date | Time |

| Logistics & ETC & Early Recovery | 3 April 2023 | 1000-1200 |

| CCCM & Shelter | 3 April 2023 | 1400-1600 |

| Health & Nutrition | 4 April 2023 | 1000-1200 |

| Food Security & WASH | 5 April 2023 | 1000-1200 |

| Protection & Education | 5 April 2023 | 1400-1600 |

Each focus group began with a brief introduction of the Sajag-Nepal project and the objectives of the workshop from the lead project investigator, Prof. Alex Densmore. This was followed with a debrief of the rounds 1 and 2 workshops and then sharing and discussion of the risk modelling outputs. The program was audio recorded and minuted with the consent of the participants.

3. Focus Group Summary

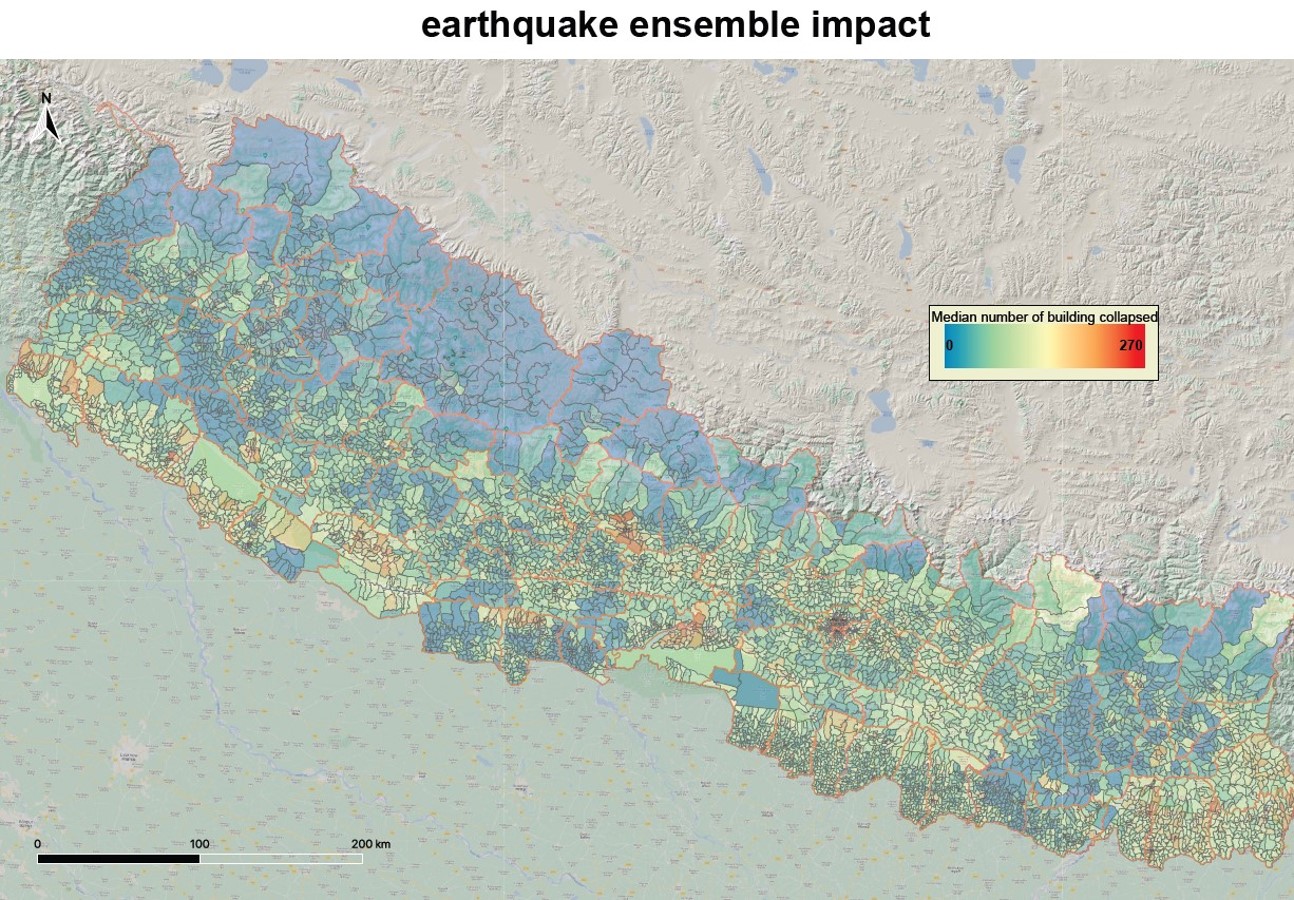

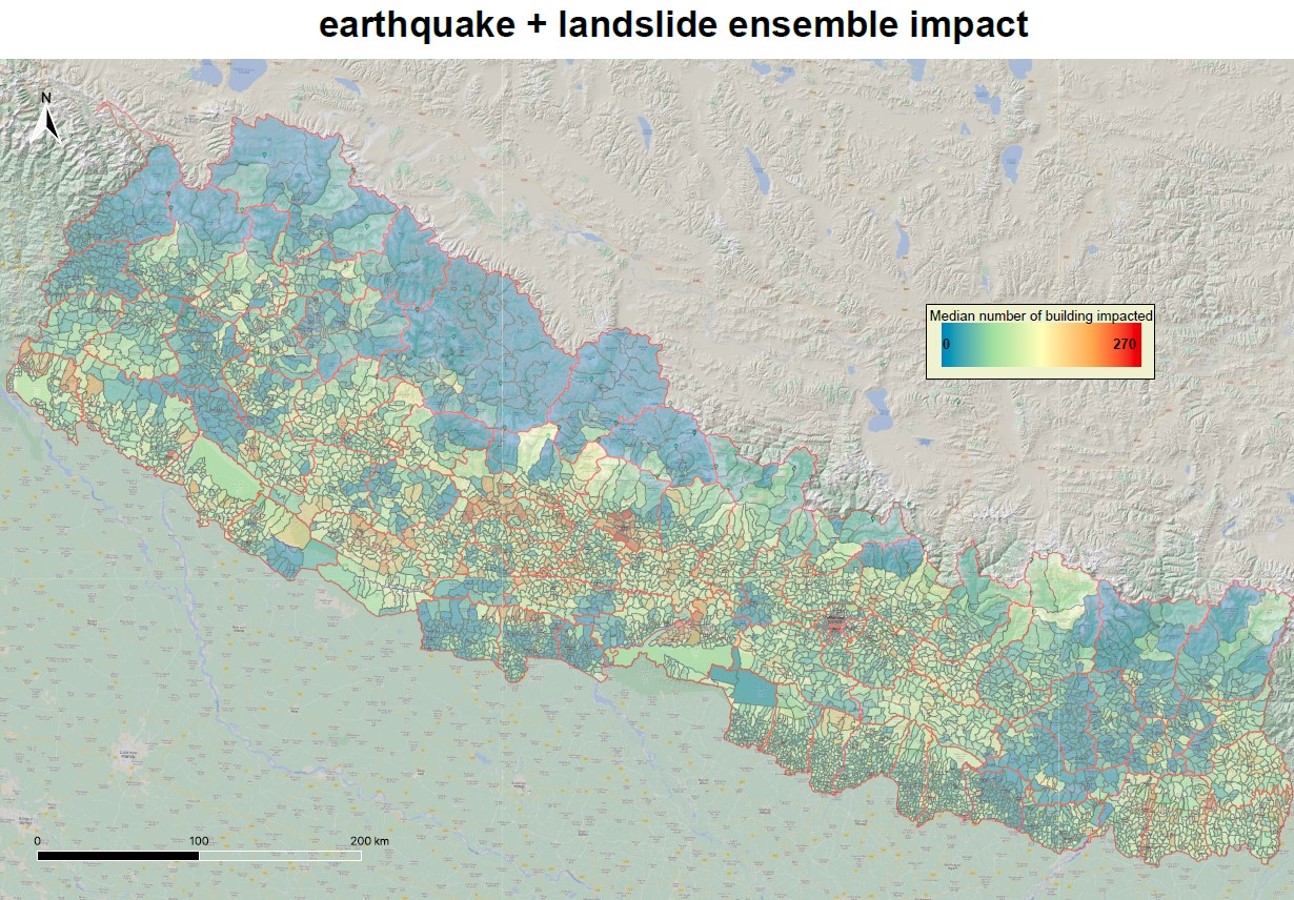

The majority of time in each workshop was focused on sharing the first results from the earthquake multi-hazard scenario ensemble. This used the same ensemble of 30 individual scenario earthquakes that underpin the current earthquake ERPP. For each modelled earthquake, impacts on buildings due to shaking damage were combined with impacts due to landslide occurrence and debris runout. Impacts were aggregated at the ward level in terms of the median number of buildings affected across the ensemble of 30 different scenarios.

3.1 Modelling Output Sharing

The multi-hazard scenario ensemble was shared with cluster members during the workshop. Two different ensemble results were presented: one with building damage due solely to earthquake shaking, and the other with building damage due to earthquake shaking, landslide occurrence, and debris runout (see below). For both ensembles, only the draft version of the median results across the 30 different scenario earthquakes were shown. This led to open round table discussion on how these model results align with the current Emergency Response Preparedness Plans, whether there are areas where the ERPP fits with the ensemble results as well as areas where it does not, and how the results could be improved and made more useful. All the clusters indicated that the multi-hazard ensemble would be very important considering that little attention is given to landslide hazard in the contingency planning process.

|

|

The ensemble results that were shared with the clusters were limited to building impacts. This gives an indication of the number of households that are likely to be affected but does not reflect the numbers of people. Some clusters requested that the 2021 census data be incorporated into the modelling to identify caseloads and estimate the size of the vulnerable population. Other clusters, however, found it useful to focus on the number of buildings and therefore households. We also discussed the integration of other attributes relevant to the clusters into the model, such as roads, critical facilities such as hospital and health centres, emergency shelters, schools, WASH facilities, communications infrastructure, market areas and open spaces.

3.2 Discussion

Regarding the type of information shared from the ensemble, almost all the clusters indicated that the use of the worst-case scenario would be ideal for the contingency plan, while the median case as presented was more useful when considering the response. There was general recognition that the worst-case scenario will not occur in every ward nationwide. In terms of federalization, a few clusters indicated that when preparing for a disaster event, the federal government could use the worst-case scenario as more capacity and resources lies with them, whereas at the municipality level, the median could be good representation for planning. The ensemble results indicated the building impacts in terms of absolute numbers per ward. When asked whether this was the best way to represent the impact, the response among the clusters varied depending on their specific focus. Some clusters indicated that the absolute number would be more useful rather than a percentage, because it showed the number of households and thus the likely demand for services. Other clusters, however, emphasized that the percentage of the total buildings per ward would be a better indication, because it showed the scale of potential impacts on the community.

|  |

Considering the spatial resolution and level of aggregation of the scenario ensemble results, clusters agreed that aggregated information at federal and provincial level would be needed. They also highlighted that, with the mandate for the local government to develop their disaster preparedness and response plans, risk information at the local level would be useful for their planning process irrespective of the uncertainties. There was a clear and consistent request for aggregation at palika rather than ward level.

Finally, the discussion explored the potential for combining the multi-hazard scenario ensemble outputs with different measures of vulnerability to create a risk map. In the scenario ensemble that underpins the current earthquake ERPP, impacts on people are combined with HDI and remoteness to create a total risk score (see the relative risk scores from earthquake shaking at http://bipadportal.gov.np). Clusters were invited to consider what vulnerability measures they might prefer in order to generate cluster-specific risk maps. While the earthquake scenario ensemble could be useful to identify the spatial pattern of potential multi-hazard impacts, there are important uncertainties on the results. The team explored the impact of these uncertainties with the clusters, focusing on two different kinds of errors. ‘False positives’ will arise in areas where the risk model predicts that impacts are likely, but none occur in the next earthquake, whereas ‘false negatives’ will arise in areas where the model predicts fewer impacts but there are major effects in the next earthquake. These uncertainties were discussed with the clusters to understand their effects on decision-making and the preparation of the ERPPs. Most of the clusters were not particularly worried about the uncertainties as, irrespective of cluster being prepared for impacts in certain areas, the cluster member organizations can be mobilized to respond to the affected area.

3. Conclusion and Next Steps

The focus group meetings were valuable to understanding the preferences of the cluster especially on the combination of level of information, spatial resolution, attributes, and vulnerability indicators that can be incorporated into the multi-hazard ensemble model in future. The meetings also provided insight on what additional infrastructure information and data could be explored for the model. The research team will use this information to refine the multi-hazard scenario ensembles and risk modelling, in order to generate the scientific evidence to support each cluster in preparing effective and improved ERPPs. Based on the discussion, risk modelling outputs based on the 2023 monsoon seasonal forecast, and that could be used in the monsoon Emergency Response Preparedness Plan, will be generated and presented at a series of follow-up workshops in September 2023. These outputs will be compared with our understanding of what actually occurred during the 2023 monsoon. These workshops will also focus on the inclusion of the 2021 census data. The end goal is to pave the way for multi-hazard scenario ensembles to be developed in time for both the 2024 monsoon ERPP and the next iteration of the earthquake ERPP.