Support for emergency response planning by the UN humanitarian clusters – Round 1

by Sweata Sijapati, Alex Dunant, Alex Densmore, and Tom Robinson

1. Introduction

A key objective of the Sajag-Nepal project is to establish a robust evidence-based approach to strengthen the national-scale strategic planning for complex multi-hazard events through the UN Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) Cluster Emergency Response and Preparedness Plans (ERPPs).

As part of the first round of engagement with the HCT clusters, we aim to increase understanding of the procedures, methods, challenges and needs of each of the clusters with respect to their ERPPs. This includes a deeper understanding of the decisions each cluster must make following a disaster, and importantly the resolution and type of data that are required to prepare the ERPPs. Combining this knowledge with recent advancements in our risk modelling methods will provide supporting information tailored specifically to each cluster’s needs. This unique collaborative endeavour with organisations in Nepal will assist the development of the ERPPs and provide more suitable and accurate information on potential impacts from multi-hazard events in Nepal.

2. Focus Group Arrangements

As part of Round 1 engagements, the research team held semi-structured focus groups with the clusters to discuss the decision-making process, the supporting information needed, and the current assumptions used for planning (e.g., caseload determination). The design of the focus groups was based on thematic similarities, tasks, organisations, and actions undertaken by each cluster as part of their corresponding ERPP.

The groupings of the cluster along with the schedule is indicated in the table below. There were a total of 53 participants (40 men, 13 women) representing the ten clusters.

| Clusters | Date | Time |

| Logistic & Early Recovery | 11 April 2022 | 1000-1200 |

| CCCM & Shelter | 11 April 2022 | 1400-1600 |

| Health & Nutrition | 12 April 2022 | 1000-1200 |

| WASH | 12 April 2022 | 1400-1600 |

| Food Security | 13 April 2022 | 1000-1200 |

| Protection & Education | 13 April 2022 | 1400-1600 |

Each focus group began with a brief introduction of the Sajag-Nepal project and the objective of the workshop from the project investigator, Prof. Alex Densmore. This was followed with a discussion of current cluster decision-making and practice around contingency planning, followed by an exercise to map the spatiotemporal resolution of the preparedness and response activities along with the information needed for cluster planning. The program was audio recorded and minuted with the consent of the participants.

3. Focus Group Summary

3.1 Discussion Sessions

The discussion focused on a set of key questions:

- What decisions do you need to take following a natural disaster? When do you need to make these? Who is responsible for making the decisions?

- What information do you currently use to inform those decisions? Where does the information come from? How and to what extent is the information used/implemented?

- What assumptions do you have to make – for example, around impact, severity, caseload, worst/average-case scenario, etc.?

- How do preparedness, response, and specific activities vary depending on the event you are responding to?

A number of common themes emerged from the discussions, summarised below.

Earthquake- and monsoon-related hazard information: almost all of the clusters relied on data from MoHA and past experience for caseload determination, but the scientific evidence underpinning that information was not always clear or accessible. In the case of earthquakes, the earthquake scenario ensemble developed previously by the research team was used by the clusters, and based on the population detail and hazard scenario the data were interpolated for caseload determination and preparedness planning. But as the scenario ensemble is based on outdated demographic data and contains only limited information on social vulnerability, the clusters were keen to understand how better scientific and social information can be incorporated in the updated scenarios. Similar information on monsoon scenarios would be welcome, as there was a sense that monsoon impacts in the hill and mountain areas are increasing in severity and reliance on past experience alone may not be sufficient in future monsoons.

Spatial patterns of hazard and risk: For many clusters, pre-positioning of supplies is constrained by pre-determined locations at either the provincial government or field offices of cluster member organisations. Pre-positioning of stockpiles, medical goods and NFI was viewed as being well managed for monsoon-related hazards, but less so for other forms of multi-hazard. Information on geology and hazard distribution across Nepal, the state of the road network, open space, and market accessibility would be highly valuable for understanding multi-hazard risk and identifying spaces for emergency clinics, temporary shelter, and temporary schools.

Data management: Access to data and its management was raised as a crucial part of both preparedness planning and response. The Building Information Platform Against Disaster (BIPAD) portal initiated by the Ministry of Home Affairs was considered by participants to be the most updated and reliable data hub in Nepal. But some of the clusters indicated that the portal is not very user friendly and this can lead to delay in the overall response. It is undeniable that during any disaster event the first informants are the local government; thus, ensuring that local government has the capacity and resources to enter data into the national portal would be very welcome. A capacity-building program at local level for the effective use of the BIPAD portal as well as data management and sharing mechanisms is needed.

Capacity: The cluster co-leads support the lead Government of Nepal (GoN) agencies in terms of mapping affected population, assessment of the commodities and other relevant fields, but the capacities of the GoN and lead agencies are often uncertain. The threshold for the cluster to intervene in the response and the basis on which the clusters or humanitarian agencies are approached is not always clear or well defined. The GoN has implemented the one door policy to minimise duplication in the response, but this in turn has delayed the response process and identification of the true affected beneficiaries.

Cluster system: The cluster mechanism was well understood and active at the federal level, but at the province and local level, gaps existed in information dissemination, coordination, and planning. There were also gaps in the regular interaction between clusters and agencies involved. There was a clear need for regular meetings and simulation exercises among the clusters and stakeholders before any disaster. This would help the clusters to share data that will potentially be useful for ERPP development and overall preparedness planning.

3.2 Timeline Exercise

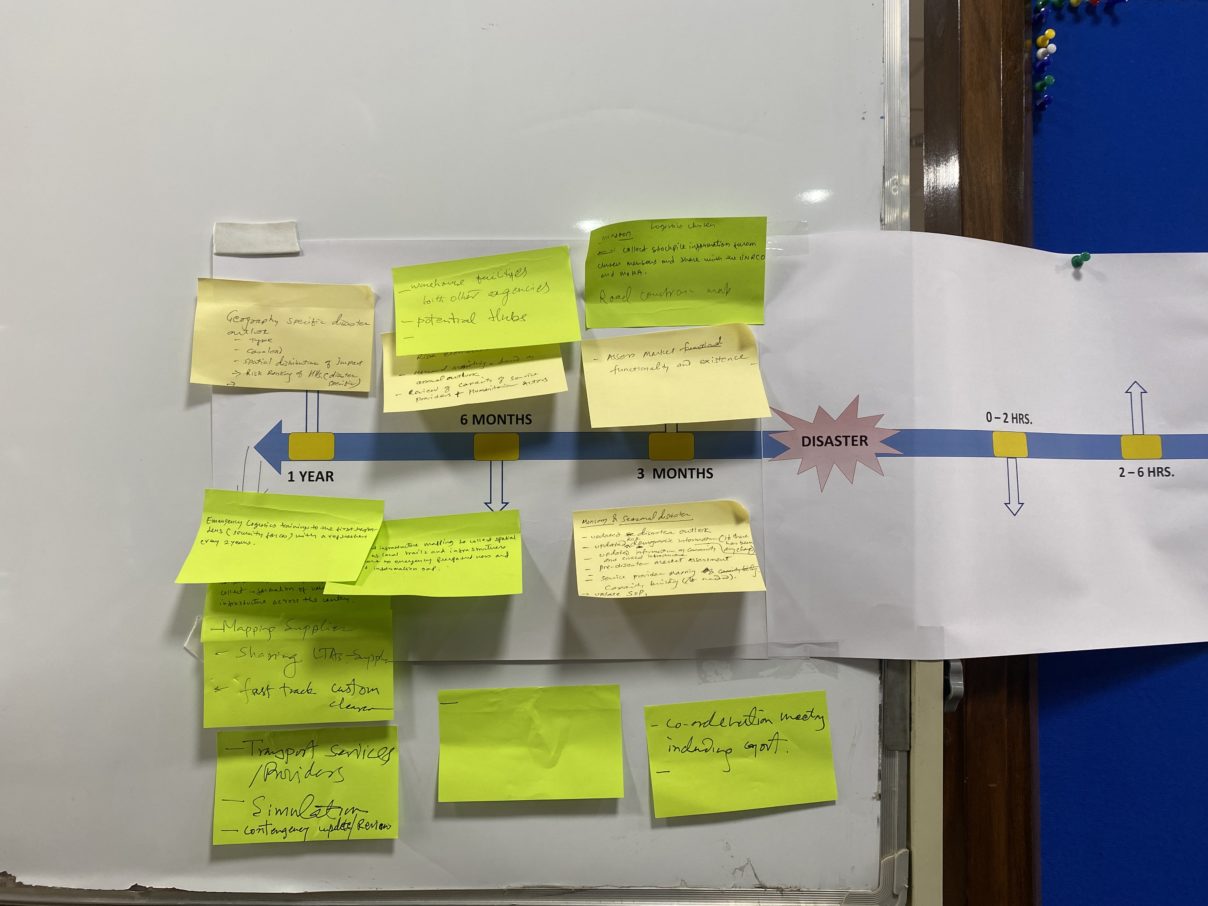

The purpose of the timeline exercise was to visualise the previous discussion session and map out the decisions being made at different spatio-temporal resolutions. The timeline was created in reference to the contingency plan and the ERPPs followed by the GoN and the humanitarian agencies. A scale of one year before and after the disaster was divided in finer time scale and the participants were asked to populate the timeline depending on what they would need for the planning process.

The evolution of the response after any disaster event was well defined and understood across all of the clusters. Thus apart from those information and activities already in place, the participants were also asked to provide their inputs on what sort of information would be needed and useful for the cluster pre- and post-disaster. Most of the clusters agreed that information on the road network and the most vulnerable areas along with disaggregated demographic information and appropriate earthquake and monsoon scenarios would be required at least annually. Many clusters highlighted that data at the highest possible spatial resolution, to house level if possible, would be valuable. Updating of contingency plans, pre-positioning and stockpiling, market assessment, capacity mapping, information on the evacuation centres and open spaces, and scientific evidence for caseload determination would be most relevant 3 to 6 months prior to the disaster.

4. Conclusions and next steps

The focus groups were valuable for understanding the procedures, methods, challenges and needs of each cluster and organisations with respect to their ERPPs. They provided insight into caseload determination and the assumptions that must be made by clusters on hazard, exposure, and vulnerability identification. The research team will use this information to refine multi-hazard scenario ensembles and risk modelling, in order to generate the scientific evidence to support each cluster in preparing effective and improved ERPPs. Initial ensemble results and risk model outputs will be prepared and presented at a series of follow-up workshops in September 2022, where cluster representatives will have a chance to explore and critique the outputs and to work with the research team on ways in which the outputs can be further improved. The end goal is to develop the multi-hazard scenario ensemble to the point that it can underpin a robust and effective ERPP framework.